by David C. Harrison

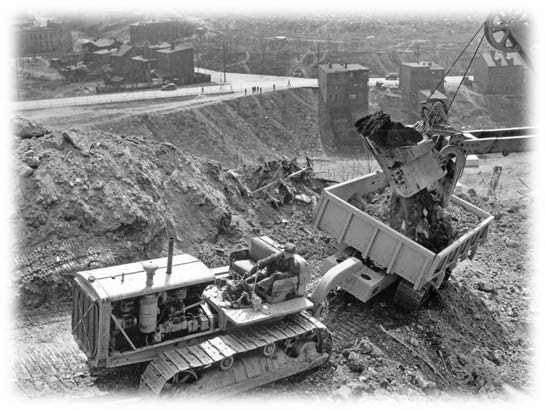

Harrison Construction of Pittsburgh, PA uses a Koehring shovel to load an Athey wagon towed by a Cat D8 tractor at the Ruch’s Hill Federal Housing site work project on May 3, 1939.

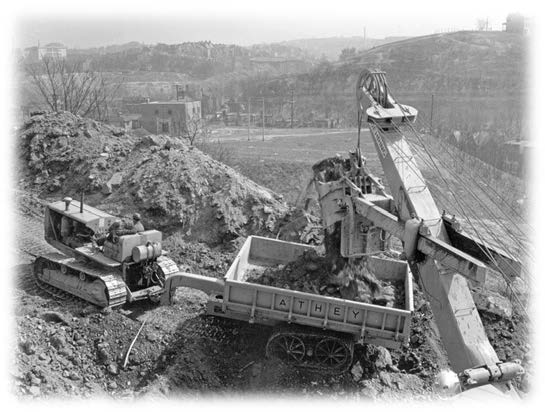

Harrison Construction’s heavy earthmoving continues at the Ruch’s Hill site on May 3, 1939.

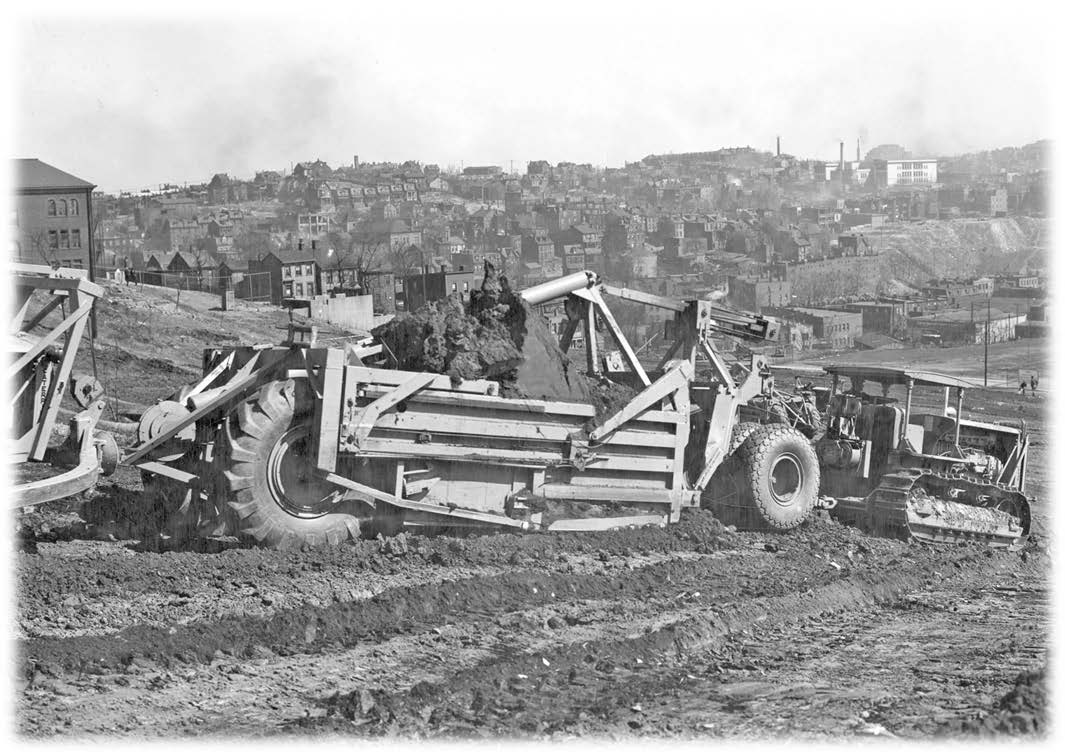

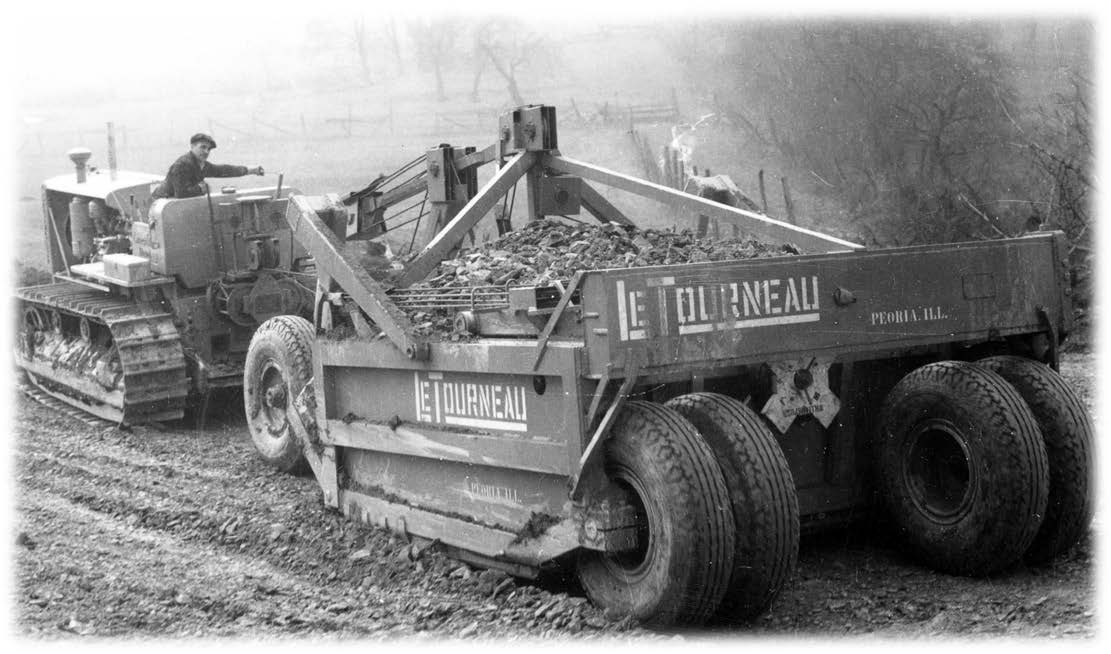

A Cat D8 tractor with an R. G. LeTourneau HU scraper is pointed downhill to load. The Ruch’s Hill project contained 800,000 cubic yards of excavation.

When my father, Max Harrison, died prematurely, in November 1966, I had assumed that Harrison Construction Company records would finally reveal to his heirs what he had been up to all those years. I had even imagined a place in our basement where I would find them. No such luck. What did fall into my hands were a few letters, advertisements and some photos, some of which keep me company on the walls of my study where I write this.

This was a disappointment, especially since I’m working on an informal memoir at Andrew’s request, my older son. Depending on what I found, I might have gone to work on a company history instead. As it is, what I think I know, or remember, about HCCo is a few fundamentals and not much else. Without you and my nephew Todd Harrison, who comes up with amazing stuff off the Web, my ignorance would be an embarrassment.

EJ Harrison was drawn to Pittsburgh from Mercer County, no doubt, by tales of great wealth being accumulated by “Pittsburgh millionaires” – Carnegie, Frick, Westinghouse et al and their close associates. He got a business degree from the Duff Institute, which, I’m pretty sure, still exists; became a bookkeeper for the Cronin & Sons Construction Co; and took it over when its alcoholic owners couldn’t run it anymore. (I was told they were found passed out near railroad tracks on the South Side.)

Max was pulled out of Penn State University before he could get a degree – he majored in civil engineering – because EJ needed him to help run the business, and likely because he saw the potential to build a fantastic, money-making family business. This, I was told, alienated Max for a time. He held a job for the Koppers Corp in Chicago, then went to work for the Pittsburgh Railways Co., and only joined his father at HCCo, he told me one day as we were driving across the West End Bridge to his office on the North Side, because EJ offered him more money.

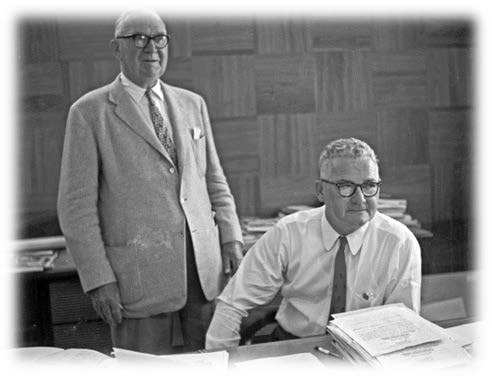

EJ Harrison standing and Max Harrison

Theirs, I took it, was a financial, not a sentimental, bond. The family aspect of it did prove to be strong in one sense, because Max shared company profits very generously, I was told, with his three sisters and their families, who were, after all, shareholders and directors. But in another sense it was weak to nonexistent: he hired his sons during summer breaks from school but made it clear that they were to pursue careers doing something else. The family business ended with him when it went under, around 1962, but even if it went on it wouldn’t have been led by a Harrison.

The 30’s were good years. EJ put the company in position to land Depression – era job-creating construction projects. He did well with government clients, small projects in and around Pittsburgh. During the war, with Max coming into his own as a company salesman, they were, according to Max, the first construction company on site at Oak Ridge, TN. And it was around this time they built Alcoa’s enormous North Plant in Blount County, TN. Max’s golf foursomes at Oakmont Country Club – he also belonged to Long Vue and probably other clubs – yielded more Alcoa projects and the creation of HCCo’s Southern Division, based at Alcoa, TN. His client base still included government agencies, but it was ties to Pittsburgh’s corporate elite at the Duquesne Club that really fueled his enthusiasm.

The Ohio Turnpike Commission offered to settle a contract dispute in the late 50’s or early 60’s. Max’s lawyer, Bill Booth, told me this when I arrived the summer of ’62 at Reed, Smith, Shaw & McClay, as an apprentice lawyer. He said Max didn’t take his advice to settle. Max put his trust in the courts instead, went on with his lawsuit and lost.

This happened at a time when his remarkable salesmanship had advanced his career in construction and politics. He traveled a good deal to meet with important people – leadership networking was his first love. The force of his personality got results. He was in demand. Too much so, I came to believe, because this profitable, admired family business, that could have lasted generations, needed closer supervision than he was able to give it.

In going through the pages of your outstanding books – from my nephew Todd Harrison I received the Ohio and Pennsylvania Turnpike editions – I was struck by the similarities in landscape and equipment, so that Harrison’s men and machinery couldn’t be distinguished without the captions. In one important respect I do believe Harrison stands out. The guy that ran it, from the mid-40’s through the 50’s, was all about character. So many of the blessings of life that came to me, and still come, came because people trusted and admired Max Harrison. He leadership-networked both his sons into a world of opportunity where, almost literally, we could have had, or done, anything we wanted.

In the summer of 1967, not long after Max died, I was able to organize a meeting at the Duquesne Club with some of Pittsburgh’s corporate elite. I wanted them to hear a presentation by an MIT professor whose students had designed a new community to be built on Boston’s Thompson Island. When it was over one of the corporate attendees, I think speaking for all of them, said he was there to honor the memory of Max Harrison.

The summer of 1954 Max set me up to work at the company’s shop at 51st St. and AV RR along the Allegheny River. The experience I got threading rods and welding supplied me with metaphors for a poem that drew the attention of Dudley Fitts, an authority on English literature at Andover. Its publication in The Mirror, with his blessing, was all that distinguished my otherwise nondescript secondary education.

That was also the summer that I traveled in a Harrison green pickup, with Ronnie, a conscientious coworker, across the border to lend a hand with the Ohio Turnpike project. Four or five of us were lifting a LeTourneau tire on the back of a pickup when I shifted my grip, thinking the direction was up when the direction was down. I heard a snap and realized it came from my left arm which had disappeared beneath the tire. Next thing I knew a doc in East Liverpool with a very attractive nurse was putting me out to set my arm.

Harrison Caterpillar D8 with a No. 90 pull scraper working on the Ohio Turnpike on June 21, 1954.

But having one arm in a sling wasn’t the end of my summer job. Max had me transferred to a project on a city block next to the old Duquesne Gardens, off 5th Avenue in Oakland, where Pittsburgh’s minor league hockey team, the Hornets, used to play. My job, when I wasn’t on lunch break checking out the Gardens, was directing traffic with my good arm.

The summer of 1954 was also when I was invited into Uncle Bill William’s shack. It stood right there in front of the shop, where equipment routed around either side of it. It was where this good man and loyal employee lived, who had simonized Max’s Buicks and Cadillacs for years at the Western Avenue office. Providing an aging employee with a place to live, a steady job and income, was a small sample of the consideration Max showed, I was told, toward all his employees, whatever their race or ethnicity.

Near Bill’s shack was a steam jenny. I used it to clean the engine of an end-of-life Harrison pickup that I would then drive crazily around the shop on lunch break. Three guys on break, eating sandwiches from their lunch pails in back, got up and scurried inside when they saw me coming. That summer I took mother’s Buick out for a spin after dinner, along US Route 40 west of Washington, PA. It was after dark. I got the old girl up to 100 mph. The same idiot was behind the wheel of that pickup, so they did the right thing.

Doing night shift at the Pittsburgh Asphalt plant, a company subsidiary, was a novelty. Dan Cowan, another good fellow, came by the house and drove me to work that night. We were supplying asphalt for a paving job, Pittsburgh’s Liberty Tubes. I remember being seated on a platform high off the ground but, unlike other jobs I was assigned, the only task I recall was staying awake.

My reward for that summer at the 51st Street shop was a trip to Knoxville to visit Betsy, a pretty girl Max’s friend Pete Gettys, a sand & gravel competitor, had introduced me to that spring. So what did I do? I rented a Chevy Impala at the airport and drove Betsy down two-lane roads at 80 mph, with my left arm in a sling and my right arm around her. Why am I still alive?

My favorite company summer job, by far, was 1957, when I was turned loose on a Caterpillar D8 rigged with a single fork in the back that I used to subsoil Max’s Tennessee River farm. 17

I would rise at 7:30, start the pony motor, then get the big engine running, get seated and start manipulating the gears and that fork. I had a pair of Chippewa boots and I got a nice tan, and by the end of the summer, Curt Hart, Harrison’s Southern Division VP, happened to be there one day and told me he would have hired me even if I weren’t the boss’s son. Being the son and grandson of hard-ass heavy construction executives, you don’t hear praise much, and that’s OK. But it was as close as I ever got to feeling like there could be a place for me in the company. For just a moment, it felt like I belonged.

In 1957 was also when I rammed the ‘dozer into a dead tree off the field thinking I would remove it when all those dead branches coming down almost removed me. Then there was the day I decided to remove a wasps’ nest from a tree along the driveway by ramming the tree with a company pickup, which, of course, wound up in the shop. And I drove an inebriated company employee back from Harrison’s annual clambake in the same pickup so fast, on a curvy two-lane road after dark, that it restored instant sobriety. Why am I still alive?

The year before, Max sent me to work with a crew paving runways, laying pipe and building an access road for an Air Force unit stationed at Blount County Airport. They had me banging the underside of dump trucks with a mallet to loosen the load when they backed up to the paving machine. I operated a Barco dirt tamper (sometimes on my foot) and helped lay pipe under a hot Tennessee sun.

But the excitement this time was provided by something called a Sheep’s Foot. This invention of the devil was supposed to pack down dirt along the edge of 45-degree fill, part of the access road. I had to navigate along the edge to do any good, and the damned thing had no brakes. Losing control would have been fatal. I recall waking up one night in a sweat, pulling up the mattress at my feet, with all my might, in an effort to apply the brakes.

Just to prove an accident could happen, I once backed up a Euclid heavy dump truck maybe one inch too far onto a depressed fill site, in Knoxville, and that’s all it took to back it right over on its side. It made the evening news, but I wasn’t injured. Why am I still alive?

That same two-lane road gave me experience operating a kidney-killer LeTourneau scraper – I scraped too deep my first shot and had to be rescued by a ‘dozer. And a grader, though the ride was recreational only. A government project inspector came along one day and needed to know if the road was properly graded. I told him it looked OK to me. Fortunately, the inspector found an engineer to answer his question and I was off the hook.

A LeTourneau Super C pan is working on the Eastern Ext. of the PA Turnpike on August9, 1949.

Another time being the boss’s son thrust me into a supervisory role when a ‘dozer operator asked if it was quitting time. I looked at my watch, as if that would settle the matter. It took a moment before I realized he was asking permission to quit. And that was the extent of this experience running a heavy construction company

I liked the Harrison cap and the company badge that was attached to it. I liked working out in the sun and around all the dust, the heavy equipment and the guys. Everyone was decent to me and to one another. The only time there was an awkward moment was when some white workers at the airport job were being a bit too casual with their conversation and a black worker showed up who could have been offended. But he got a fast, gracious apology and, I don’t think, would have taken offense anyway. It wasn’t an ugly moment at all, just awkward.

Otherwise, a whole lot of classy individuals were taking care of their jobs, working well together and being professional. The one instance where I clearly didn’t belong was when I was replaced in the cab of the Euclid one day by a union driver. He just showed up, got in the cab on the passenger side and indicated he was taking over.

That was my one experience with labor-management relations in mid-20th century America. It was the one time where I felt just a little of the pressure company management, and companies around the country, felt from an aggressive labor movement. I didn’t take sides – poets who dig ditches in the summer to make a buck aren’t exactly involved – but it did make an impression. I could see Max’s side of it a little better, but I also respected labor’s side of it. If that irritated Max what fun it was to hear him complain about one of my cousins he employed who joined a union picket line at a Harrison project. Why is my cousin still alive?

Eighty-five bucks a week. That’s what we were paid, and it was more than most of my classmates probably earned at their summer jobs.

Construction jobs paid well then and they still do. Construction, mining, and manufacturing – these are the bedrock jobs for a thriving middle class, and I had a little part of it.

What ties my career to my father’s career after my formal education wasn’t anything to do with business, at the office or in the field. It was leadership networking. It’s where his career really took off, and mine. At least insofar as I enjoyed it and got any results. His networking got results for the company, elevating it from just another construction outfit to one that was noticed. It was, I’m certain, because of the quality of its work, the character of its chief executive, and how vividly he brought himself and his enterprise to life.

I’m damned proud to be a Harrison, and a large part of it is because of him, and because of his company.

His networking also got results for him, because he hugely enjoyed it. When he would come home from work, busting through the back door in his straw boater, a man of good cheer and upright bearing, I could tell he had come straight from the Duquesne Club. He had been Building the Best for the Best, his company motto. He had been living it. He wasn’t a major figure around town, exactly, but he was a force unto himself. I wish you could have seen him, known him.

And I wish he could have known you. Your work is clearly a labor of love, and with these recollections, I hope some of my respect, my appreciation, comes through. I hope some sign comes through that, if Max and EJ were here, they both would be feeling pretty good that somebody out there was paying attention.

Thank you so much for your very kind inscription, Enjoy the history as your family helped make it. Max and his father did make history. All their employees, and all the companies and their employees featured in your books, made history.

I’m so glad I don’t have to root around in the basement to find a record of it.

Thank you, Edgar. Keep up the good work!

Sincerely, David C. Harrison

Harrison Construction uses Caterpillar D8 tractors with LeTourneau pans to handle heavy earthmoving at the Kanawha Airport in West Virginia on May 28, 1945.

Caterpillar RD-8 tractors with LeTourneau bulldozers and scrapers grade the North Park Playground in Allegheny County during May, 1936. The project required excavation of 460,000 cubic yards.

Two LeTourneau Model A Tournapull scrapers were used by Harrison Construction on this highway relocation between Johnstown and Southmont, PA, circa 1940.

A Euclid TS-24 scraper is push loaded with Euclid TC-12 and Caterpillar D9 tractors in this cut section along the Erie Thruway (Interstate 90) near Platea in Erie County, PA, circa 1958.

N. T. "Whitey" Franklin, Vice President in charge of construction, surveys work at the Pittsburgh Airport in 1960. The massive 7.9 million dollar contract called for the excavation of 8 million cubic yards of material to build a new runway. A Marion 111-M shovel is loading a B Tournarocker in the background.

EDITORS NOTE: David C. Harrison upon reading accounts of Harrison work in two of my road building books wrote the poignant well-crafted letter describing the human side of growing up in a heavy construction family business. It is used here with his permission.

"Harrison Construction" first appeared in "SHOVEL" Winter 2015, an official publication of the Historical Highway Heavy Civil Construction Association. 10415 Turnstall Road, New Kent, VA 23124. Edgar A. Browning, Editor and Publisher. (804) 932-8232.

Enjoyed reading this wesite. My dad worked for Harrison con. Co. Don't know when he started, he worked on site preparation at Oak Ridge, Tn, McGhee Tyson air force base and the Alcoa site, Ohio turnpike, and greater Pittsburgh airport. I went to work with my dad one Saturday at the airport, spent my day exploring and catching tadpoles in a mud puddle. Fond memories.